Appropriation art: concept or theft?

Every few years, appropriation art “bad-boy” Richard Prince releases a new body of work that pushes the boundaries of what constitutes an original artistic concept and what constitutes theft of ideas. Every time, the controversial works prompt a discussion as to what legally defines appropriation art, and what ethically defines it on a cultural level.

At its most basic, appropriation artists take another artist’s creative product and transform it into a new piece. As opposed to referencing works cited or quoted in a written work, appropriation artists are typically in no way required to make reference to the original piece’s context or artist.

Legally, appropriation of a creative work must meet several requirements, which often depend on local laws. First of all, the transformation element is essential. In the U.S., if the new work transforms the original piece, it falls under “fair use.” This means that the original work is used to create a new work, therefore, the appropriation artist is protected from prosecution. Essentially the piece has been re-contextualized to hold new meaning.

Often, this is accomplished by adding something to or changing the original artwork’s presentation. In Prince’s notorious “Canal Zone” series of 2008, the artist took photographer Patrick Cariou’s published photos, blew them up to large-scale, and added additional painted and collaged elements on top of the photos. Cariou sued, claiming that his original works were being used for pieces that were being sold for millions of dollars, but the court found that Prince’s work met the requirements for fair use.

While Prince has been pushing the envelope when it comes to appropriation since the 1970s, many famous artists have used the technique in their works – some even finding themselves faced with lawsuits, like Prince. Barbara Krueger, whose large-scale text works often use collage images for the background, won a 2000 case filed against her by a photographer, and Jeff Koons was victorious in a 2005 case brought against him, also by a photographer.

In fact, appropriation goes back even further into art history. In the early parts of the 20th century, Marcel Duchamp made waves in the art world with his readymade objects. In his works, Duchamp would use objects like bicycle wheels and shovels, and present them as artistic concepts, essentially transforming them by presenting them in a new context, and signing them as he would a traditional painting or object.

His contemporaries working in cubism like Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque also experimented with collaging existing items into a work – without necessarily even altering the original objects. Surrealist and Dada artists continued this experimenting with using appropriated objects in different media.

By the mid-20th century, artists like Robert Rauschenberg used silkscreens of texts and images in collage and paintings in addition to repurposing objects like beds for installations that predicted the trend that would re-emerge in the 1990s. In the 1970s and 80s, artists like Elaine Sturtevant recreated original artworks like Andy Warhol’s Flowers (1965) by hand painting them.

While the legal definitions of appropriation offer some guidelines, there is still a split in the art world as to whether appropriation art is ethically acceptable. For example, Prince’s most recent series of others’ Instagram photos on large format canvases incensed many who were featured in his works in addition to a number of art critics, because he didn’t ask for permission to use their images while selling his versions for six-figure sums. On the other hand, Sturtevant’s work was celebrated in a 2014 career retrospective at New York’s Museum of Modern Art.

It’s likely that whether appropriation is acceptable or not will be debated for years to come as technology allows for even more ways to access and manipulate others’ creative products. That being said, these works tend to do just fine in the global art market, and many are highly sought after by collectors in some ways because of their controversial nature.

By Rachel Cohen, LCAT, ATR-BC

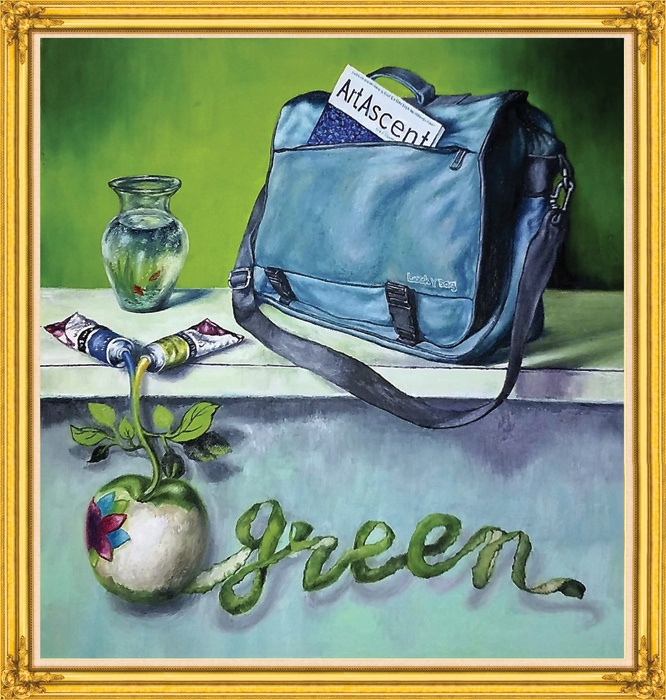

Pictured above (frame excluded):

Apple and Bag #1 by Glenn Leung